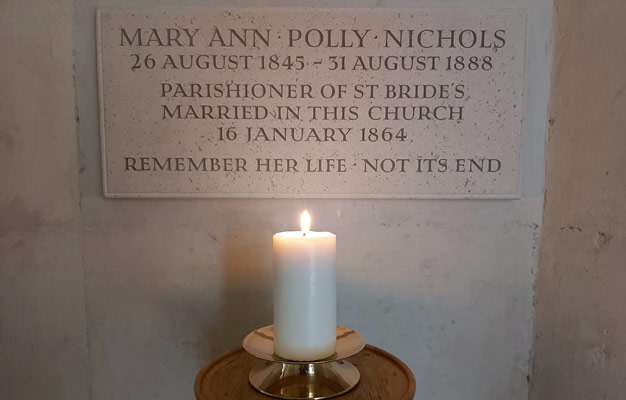

Almost the final task that we were able to complete here in this church before our doors were forced to close at the first lockdown last March, was the installation of a new memorial just inside our west doors. It is a memorial commemorating a Victorian woman called Polly Nichols, who was born in our parish and was married here in 1864.

Her epitaph concludes with the words: ‘Remember her life, not its end’. Because, tragically, the sole reason why Polly Nichols is remembered today is because of the manner of her death – she was the first known victim of the Victorian serial killer nicknamed Jack the Ripper. Yet every human life deserves to be remembered for more than simply its ending. Polly was a wife and a mother of five surviving children; she came from a respectable working class home, and she spent longer in education than either of my own grandmothers. Yet history remembers her has nothing more than a murder victim, or ‘just a prostitute’ – which is equally appalling because it may not in fact be true.

It has been immensely important for us to be able to re-tell her story, and play our part in recovering her identity as a precious child of God – and in the process, to be reminded of all the women, past and present, who have ended up living in destitution, or who were affected by sexual exploitation.

As chance would have it, today, 30th May, is the date on which the Church of England calendar commemorates another Victorian woman, whose life overlapped with that of Polly Nichols, and who was herself deeply concerned about issues of sexual exploitation. Her name was Josephine Butler.

Josephine Butler was born in 1828 and in 1852 she married an Anglican priest. She was a devout woman of faith. She became increasingly concerned at the way in which society treated women, and worked tirelessly for improvement in their education – but she was particularly concerned about those who were driven to prostitution through dire poverty. A specific focus for her outrage was the so-called Contagious Diseases Act, which was linked to the government regulation of prostitution.

The theory was that men could not be expected to be sexually continent when separated from their wives, so it was natural for them to seek the company of prostitutes. Therefore it was the role of the government to try and ensure that such women were free from sexually transmitted diseases, in order that members of the armed forces, in particular, were not put at risk of infection. In 1866 a special corps of police was established to enforce this, by creating and keeping a list of licensed prostitutes. These unfortunate women were forcibly required to undergo regular medical examination – but, worse still, these police powers were widely abused, and led to appalling and degrading treatment of women who were simply poor. This alongside the basic injustice – that it was the women alone who were penalised and degraded by this act. Her campaign was successful and led to the repeal of the Act in 1883 (just four years before Polly Nichols’ death).

It was not only the courage and commitment of Josephine Butler that made its mark – when she addressed a select committee of the House of Commons, it is said that her sincerity and her dignity left a profound impression. Drawing a parallel with the abolition of slavery, she appealed to overarching humanitarian principles, saying this:

We take our stand entirely and purely on the principle that the State must not regulate prostitution; and no results given to us from year to year, as they are, not reports of this present Committee, will in any respect or in the smallest degree alter our position, because we take our stand upon principles which are eternal.

Josephine Butler was a woman who knew that her Christian faith left her with absolutely no option but to challenge the degrading treatment and the appalling injustices committed against women in the society of her day. She had to act because her faith compelled her to. Because one of the curious paradoxes of the Christian faith is that we only truly grow inwardly by engaging outwardly. Christ was for ever on the move, healing the sick, cleansing lepers, engaging with the lost and the lonely and the vulnerable and the forgotten and the marginalised and giving them hope because he gave them dignity. Our Christian faith requires us to look open ourselves to the pain of the world, and to act upon it.

It is for that reason that it has been important for us to connect our link with Polly Nichols with the work of the charity Beyond the Streets that supports women who are affected by sexual exploitation today.

I shall close with a special prayer for today, commemorating Josephine Butler, social campaigner and a model of inspiration to us all.

God our redeemer,

who inspired Josephine Butler to witness to your love

and to work for the coming of your kingdom:

may we, who in the sacrament share the bread of heaven,

be fired by your Spirit to proclaim the gospel in our daily living

and never to rest content until your kingdom come, on earth as it is in heaven; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.