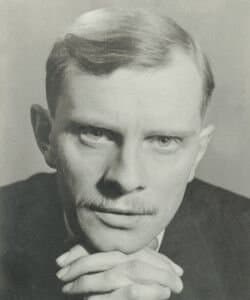

I am Mimi, daughter of Hugo’s friend, the 4th-generation Bristol wine merchant John Avery. For 30 years, my late father liaised closely with Hugo through the International Wine & Food Society, and it was via this friendship that I came to apply for the position of Member Services Secretary of the Society, working as a duet with Hugo for just over 5 years.

You’ve heard from Jim Surguy about Hugo’s adventurous and often hilarious advertising career, which began in 1957 when he was 31, and was preceded by his equally colourful Managing Directorship of Finders, Ltd, when he became quite well-known as ‘Mr Knowledge’, thanks to Finder’s universal swiftness at providing anything from 300 male toads to the address of an ice-skating rink in Baghdad.

Hugo’s interest in eating well had begun much earlier, as a boy at home in Streatham, South London and surprisingly, at school, where the priest in charge of boarders scoured neighbouring farms for good ingredients. He first tasted wine — either a generic red Entre Deux Mers claret or the rather grander Mouton Rothschild (Hugo liked to tell a good story, and details could vary!) — at the age of 21, when the Bishop of Coutances came to luncheon at the Normandy château of his friends the Montgermonts, where starry-eyed Hugo was staying in 1947 — his hosts’ habitual alcoholic drink being cider pressed from their own apples.

That same year, Hugo stood in for an ailing comrade from his end-of-war, Royal Navy days at the Wine and Food Society’s first post-war Christmas dinner at the London restaurant Quaglino’s. He was rather ‘awed’, he writes, ‘by the ambience and, after 8 years of austere diet, its creative cuisine and what, even as a novice, I could recognise as good wine. I was also a little overpowered by some of the famous names on the seating plan. ‘ One of these put him at ease, and introduced him to the then 70-year-old André L Simon, transplanted Frenchman and former champagne salesman who had founded the Society in London in 1933, and by 1939, expanded it to many towns in the UK, to several American cities, and even Paris.

Simon found Hugo a place at his own table and, he goes on, André’s ‘parting words that night were “I have not long to live. You must carry our torch when I am gone”. Perhaps the inaccuracy of the former prophecy — Simon survived for another 23 years — retarded vindication of the latter, as,’ Hugo observes, ‘I did not become the Society’s International Chairman until 1978.’

In the meantime, he was ‘entranced’ by Simon’s ‘simple philosophy’, that ‘food and wine are gifts of the Creator which should be appreciated for their true value, and ought to be within reach of everyone. It was cultural, not hedonistic’. This was a meeting which shaped the course of Hugo’s adult life.

In 1948, he went on from that memorable dinner to buy his first bottle from ex-RAF man Laurence Webber at Green’s wine merchant’s in London’s Royal Exchange. Hugo doesn’t seem to have recorded its identity, and Laurence, still alive at nearly 90, and for many years a Master of Wine, doesn’t recall. Though unable to join us today due to ‘limitations of the flesh’, Laurence has e-mailed that ‘it must have made a lasting impression, as Hugo introduced me to several of his contacts over many years as the person who sold him that first bottle!’

Not a bad start. In due course, Hugo assembled an enjoyable and ever-expanding collection, writing that ‘In the ensuing few years, I drank wine at every opportunity, and even dared to serve it at home, my father (with whom he lived until his first marriage) did not approve of what he believed was an unconscionable extravagance. I remember once serving some claret which I had painstakingly kept under a running tap for an hour as we did not have a fridge, and on another occasion, proudly poaching dover sole in the red burgundy called Chambertin! But one learns by one’s mistakes, as they say.’

During the three intervening decades from opening the Green’s bottle to assuming the demanding but honorary task of the Wine and Food Society’s International Chairmanship, Hugo developed strong ties with that organisation. He therefore accepted, a half century after its 1933 creation, the Society’s invitation to assume its central management, a paid employment and transformative task to which Hugo devoted fifteen dynamic and forward-thinking years. Under his leadership, the Society thrived, and branches proliferated in many parts of the world. On retirement in 1998, he left the organisation in good shape, with adequate assets in the bank, good premises at the Lansdowne Club in Berkeley Square, and a small but dedicated staff.

During this time, Hugo also edited nine issues of the Society’s Journal Food and Wine, became a favoured broadcaster and public speaker, and wrote prolifically about his chosen subject.

On the strength of producing 7 editions and reprints of the Wine Record Book, co-authored in the late 1960s with his friend Norman Riley, and occasional work for the 1970s’ gastronomic press, Hugo had been proposed for the Circle of Wine Writers in 1977. After his election, his Circle mentor told him, with a chuckle, that another member, as difficult as she was distinguished, objected on the grounds of his ‘youth and inexperience.’ In the Circle’s Brief History, written by his colleague Christopher Fielden in 2005, Hugo observes, with his characteristic modesty and deft sense of humour, ‘At least I have been able to overcome the former!’

In later years, the Circle made him a life member, as did the Guild of Food Writers, which he founded in 1984.

Hugo loved and collected gastronomic literature, gathering books and ephemera as he travelled the world. After André Simon’s executors sold Simon’s pre-1900 volumes, Hugo arranged for the remainder to go to the City of London reference library at Guildhall. He also presented his own collection of menus and wine catalogues, and was involved with Guildhall’s acquisition of part of Elizabeth David’s estate. There followed the books of the Institute of Masters of Wine and the Worshipful Company of Cooks, among contributions from other provenances, so creating a precious resource for future generations.

I started working at the IWFS on the 4th July 1994, and 20 years later, I clearly remember Hugo’s energy and enthusiasm – the glint of mischief behind his ever-present monocle, his love of the Lansdowne Club, and the buzz of helping our members with both basic and strange requests.

Hugo was joyous, and the soul of old-fashioned, high-spirited courtesy. Among messages to his wife Tish from his legion of friends, vinous and otherwise, several stand out: ‘He had the enduring skill of making one feel welcome on all occasions, and that you were the one person he really wanted to talk to. His intelligence and breadth of interests were extraordinary’;

And then:

‘For a man with so much to say, he was a good listener — and that is a gift not given to many. Always just the right little question or conversational nudge to keep the stream trickling along. He was a natural storyteller, and I hope there’ll be stories aplenty at the celebration.’

And finally, from his St Thomas hospital cardiologist:

‘I remember your husband’s visits to clinic vividly and fondly. It’s seldom the patient that makes the Dr feel so much better!’